While many people know that the Williamsburg County Courthouse was designed by Robert Mills, few understand how important he was to American public architecture. In the March 3, 1929, issue of The News & Courier, Laura C. Hemingway took an in-depth look at Robert Mills' career, including interesting commentary on the Williamsburg County Courthouse. Laura Cromer came to Kingstree from the upstate in 1913 as principal of the graded and high school. After marrying Dr. Theodore S. Hemingway on October 9, 1915, she wrote many interesting articles, usually on local history, which appeared in newspapers and magazines around the state. Here is her story on Robert Mills:

A century in the Mother country is a short period of time in architectural cycles. There buildings stand for ages to increase in charm as the years roll by. In America it is the reverse. Few houses of any kind first erected in this country have been left to bear testimony to the influences of the architecture of other countries and other ages. This is due principally to the ever growing demands of progress in the new world.

But all over America now antiques are gaining recognition from the observant and discriminating. Old furniture has been reclaimed from attics; ancient bits of glass have been brought to the light of day once more; and whereas a generation ago an old building was ruthlessly torn away to make place for one better fitted to suit the needs of an increasing population, sentiment and appreciation have begun to reach forth detaining hands and rescue many of these from destruction.

As the nation settles down to peace following a war, it is inevitable that certain students of this esthetic in architecture, as well as in other things, should awaken to the fact that here in America may be found structures that do credit to any nation. Recognition of such may be attributed to a number of things. Chiefly, it would seem to the increasing system of roadways and every growing number of automobiles. No longer is the American public content to sit beside its fireside. When the snows of the North become too heavy, a stream of tourists begin their southward trek. And when the southern summer sun beats to mercilessly upon the natives, they, in turn, are ready for their pilgrimage to mountains and lakes.

And thus it is that "one touch of nature makes the whole world akin." People want to know facts now as perhaps they have never wanted to know before. They all but demand the marketing of historic sites. They seek out odd corners where heroes lie buried. And they notice distinctive buildings and enquire as to the age of such and the origin.

Few men left more monuments to their names in the concrete form of stone and wood than did the architect Robert Mills. Planat's Encyclopedia d'Architecture and also the Dictionary of Architecture, both issued by the London Architectural Society, allot more space to Robert Mills than to all other American architects combined. Yet, in spite of his foreign recognition, and of the fact that he designed more public buildings and monuments in this country perhaps than any other one architect, his name has been all but forgotten by the latter generations. Although he was a prolific producer of plans and designs, he rarely placed his signature to any. For that reason, others have been given credit for the work he has done in more than one instance.

Robert Mills was born in Charleston, South Carolina, August 12, 1781, and died in Washington, D.C., March 3, 1855. He was the son of a Scotsman, William Mills, of Dundee, who came to America in 1770. Robert Mills' mother was Ann Taylor, a descendant of Landgrave Thomas Smith, provincial governor of South Carolina in 1690.

Robert Mills

He received his education at Charleston College. About 1800, he became associated as an apprentice with James Hoban, a Charleston architect who maintained offices in Washington, D.C. and who designed the White House. Young Mills was sent to Washington, and it was there he met Thomas Jefferson, who instantly became interested in the young architect from the South. So interested was Mr. Jefferson that he invited Robert Mills to visit him at his estate at Monticello. While there, Mr. Jefferson decided to build the mansion and so great was his confidence in the ability of Mills that he assigned the drawing of the plans to him, preserving for himself only the details.

It was probably while on this extended visit to Monticello that he met Miss Eliza Barnwell Smith, daughter of General Smith of Hackwood Park, Virginia, who later became his wife.

Robert and Eliza Mills.

Mills must have been an indefatigable worker if one would judge by the number of worthwhile places designed by him in the vast expanse of territory. This ranged from South Carolina up through Washington, Philadelphia, Baltimore, New York, and out as far as New Orleans. And that more than a century ago when travel was tedious, long, and drawn-out.

In addition to his architectural work, he was a prolific writer along reformative lines. Strange though it is, in this he seems to have been a prophet without honor in his own country. Latter years have brought to pass some of the issues for which he advocated, but during his lifetime, he seems to have received more censure than praise.

He possessed a keen insight into the economic conditions of his home state and tried to lift up his voice to bring about an era of prosperity established upon sane and safe principles. Whenever he offered a suggestion for the betterment of conditions, he accompanied it by practical working plans. He was an advocate of river and canal development in South Carolina, this to continue across the mountains to the Mississippi River, eventually to become a network for inland navigation. Taking the Broad River as an example, he said:

"To the lover of his country, the head of this river induced a most interesting train of thought, and when he ascends the mountains where the western branch of the Broad (there called Green) River intersects it, he will behold the waters of the extremes of the Union almost interchanging and inviting the hand of industry and art to unite them–unite us and you bind the political destinies of your country in bonds of indissoluble peace and prosperity."

Mills further proved himself a prophet in predicting the "steam carriage" as a forerunner of the automobile in his Substitute for Railroads and Canals, published as early as 1834.

But in nothing, speaking in economic terms, was he so interested as in the reclamation of his native lowlands. In his Statistics of South Carolina, he declares:

"Independent of the incalculable benefits which would result from it in points of health and comfort to the inhabitants, the finest lands of the state would thereby be brought in cultivation, and the way opened for increasing the population of this section of the state, thus adding to the physical power of the country."

Mills Atlas of 1825 contains individual maps of the 28 districts of South Carolina. Produced from a special appropriation of $64,670 during the period of 1816 to 1825, these maps are signed by 22 surveyors. Only those of Darlington and Marlboro were left unsigned. These were probably the work of Robert Mills.

Charles C. Wilson, architect of Columbia, to whom the writer of this article is indebted for an unlimited supply of information concerning the subject of this sketch, says in speaking of these maps, "I have had occasion in the cause of my practice to test the accuracy of these maps by extensive and precise surveys in thirteen of the twenty-eight districts, and I have yet to find the first material error or omission. Every stream, lake, road, hill, swamp, or other permanent landmark I have found to be exactly as represented, and no surveys or maps haves since been made which will compare with this work of a century ago in completeness or precision."

In architecture, also, this same thoroughness and precision is so noted that the stranger in passing one of his buildings is quick to notice something distinctive about it and begins to make inquiries concerning it.

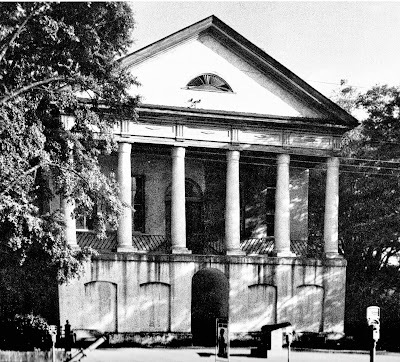

In the Charleston Courier of February 18, 1822, Mills' signature appears over an advertisement for proposals for building court houses at Greenville, York, Newberry, and Kingstree. Of these four court houses, all of which were similar in design, only one is left today. That is at Kingstree. This is still in use as originally planned. It is typical of Mills' style, showing its "massive Greek Doric" columns rising from a second story vestibule to the portico roof. It may be said that his characteristic, the portico and massive columns almost invariably found upon his public buildings, is Mills' signature, which he seemed averse to signing with pen. It was unnecessary!

Edward Hooker in his diary of 1808 spoke of such columns rising from the area of the chapel at the South Carolina College, now the University, with "considerable majesty, giving the room an appearance of grandeur." This is the impression left upon the minds of tourists passing through Kingstree when they view the old court house, standing in stately dignity among its live oaks on its expanse of green sward opposite the hotel. Officials within this house of justice claim that strangers frequently come there seeking to know something about this classic building. And strange to say, they have been turned away uninformed, for this work of architectural art has simply come to be accepted as "one of the old houses" of Kingstree!

Columns and portico of the Williamsburg County Courthouse today.

As it is typical of others designed by Mills, it is not amiss to give it some detailed description. Its original proportions are perfect. Two stories in height, the first floor being built on a level with the ground. Through the center runs a corridor with a vaulted ceiling of considerable height, and with a paving of slate flagstones for a floor. Where these flagstones came from in that day when the carriage of such was no easy matter has never been satisfactorily determined. It is generally supposed they were brought over from the Mother Country. Certain it is that they do not abound hereabout.

A view of the vaulted hall ceiling through the door of the Courthouse.

A view of the vaulted hall ceiling through the door of the Courthouse.

On each side of this corridor are the office rooms. These are well-proportioned, having vaulted ceilings and recessed windows or French doors, some of which still retain their heavy inside bars. The floors are concrete. The second story, or court room, is reached over outside stairs at the end of the portico. The steps are deep slabs of solid slate stone. They bear evidence of more than a century's wear, and therein lie many stories for the imaginative. The balcony has a wrought iron railing across the front.

Certain of the older citizens in Kingstree remember this building catching fire and burning the roof. Valuable papers were removed to safe quarters, it being feared the building would be destroyed. But evidently those of that generation were not acquainted with Mills' hobby to make his buildings as nearly fireproof as possible. After several days, the officials realized the building would not burn, and the papers were restored to their shelves. However, it is said that certain old documents have never been found since the fire. They were possibly destroyed or misplaced.

So fireproof was Mills' work that he was chosen to design two fireproof wings to Independence Hall in Philadelphia. This he did, not varying the style of architecture an iota, in 1810, while he was still under 30.

The walls of the Kingstree courthouse are of solid brick 30 inches thick. Two rooms across the back have been added in recent years, but this was done in keeping with the original architecture. In 1884, the building underwent minor remodeling. A stucco outer surface was given the brick. Near the arched entrance to the lower story is a tablet bearing the names of the commissioners at that time. These are J.W. Gamble, G.P. Nelson, and S.I. Montgomery. The contract for the building was given to a Mr. Hoover from North Carolina. At the same time he constructed in the Cedar Swamp section a commodious residence for John Ervin Scott, father of Dr. D.C. Scott. His work bears the earmarks of sustainability.

The remodeling following the fire was under the direction of J.K. Gourdin, an architect of some note in his day. He was accorded considerable notice in his profession by his remodeling of St. Michael's church following the earthquake. Certain parts of the brick walls had been thrown out of line. Mr. Gourdin succeeded in reclaiming them with no material damage to the structure.

Kingstree's courthouse is built upon the early muster grounds. The titles were held up for some time due to the inability on the part of those in authority to remove from the premises an old "squatter." it was after his death that clear titles were secured to the entire plot.

The courthouses in York, Newberry, and Greenville designed by Mills in 1822 have been replaced by modern ones of more imposing structure to meet the progress of the 20th century. The original building in Greenville has been attributed for many years to Joel R. Poinsett. This due, perhaps, to the fact that Mills was associated with Poinsett and Abram Blanding on a Board of Public Works about the year 1820. When this building was torn down a few years ago to make room for the 10-story Chamber of Commerce, many who were interested in its origin hoped some light might be thrown upon it by means of the contents of the cornerstone. There was no cornerstone. All the more evidence that Mills had designed the building. There, too, were the usual side steps rising to the upstairs portico. The iron railing along these steps, it is said, was designed and made by Mr. Cauble, Greenville's pioneer blacksmith.

The Greenville courthouse boasted a rather ordinary little tower entirely out of keeping with the original design. This was added in later years to house a town clock which was never installed, the money collected for this purpose having disappeared after the death of the collector. Many in Greenville regret the utter razing of this old building. But the growth of the "Mountain City" has been so rapid that two courthouses have been built since Robert Mills designed his.

The Mills' designed Greenville County Courthouse. It was demolished in 1924.

The York courthouse was burned in 1893, but some parts of the original foundation were used for the new building that replaced it. But here again progress has seen to it that an entirely new courthouse was built in 1914 on the old site.

Newberry has replaced her Mills building with a modern one of more pretentious dimensions.

Mills also designed the original courthouse at Camden, as well as the Presbyterian church, and the De Kalb monument. While Camden has answered the call to the advancement of civilization and built a modern courthouse, she has not discarded the old one. It still stands on the edge of town, typical of the work of a great architect. Its former office rooms have been used to house impoverished ones at various times. Many will remember the aged Negro, "Uncle Billy," who lived until his death in one fo the back rooms. He was ministered to by the charitable women of the town. Once when the old fellow complained of being bothered by rats, these women had his dilapidated wooden floor removed and found beneath it one of cement in perfect condition. No doubt this was the original floor and some office holder had placed the wooden one over it later, thinking it less cold. The ladies also found rats enough to infest any Hamlin town.

Old Kershaw County Courthouse.

In Charleston, Mills designed the Baptist church on Church Street below Tradd; the Circular church which is the first building in America surmounted by a dome and crowned by a "lanthorn light," and one of three circular churches designed by him in America, the other two being in Philadelphia and Baltimore; a fireproof office for the public records of Charleston; a four-story wing to the public prison on Magazine Street; and nine fire- and bomb-proof powder magazines.

In Columbia, he was responsible for the Asylum building, the plans of which were found comparatively recently in an attic in Massachusetts; Rutledge College dormitory and chapel at the University of South Carolina; and the Maxcy monument.

The fact that he designed the Washington Monument in Baltimore, which gave to that city the title, "The Monument City," was established after some difficulty. He also designed the Treasury Building, the Washington Monument, the Patent Office, and the old Post Office Building in Washington, DC.

In fact there seems hardly a city of any significance at that time that did not bear evidence of his skill. He as been called the preeminent leader of the Greek revival style of architecture in America. He is said to have taken the Parthenon as his ideal. Simplicity of design was his keynote. He relied for his effects on well-chosen proportions, avoiding details and ornamentation.

The Architectural Dictionary of London credits Robert Mills with suggesting the railroad from Charleston to Hamburg. Old files of the Scientific American reveal that he first proposed a transcontinental railroad, advocating the monorail as a medium of excessive speed with safety. It was during his service on the board of public works in his native state that he was active in building the state road from Charleston to Columbia and thence to Greenville. It was his purpose to connect South Carolina, North Carolina, and Georgia with a system of canals. Thus it was that the Seneca River was improved and made navigable 26 miles to six miles above the Pendleton Courthouse.

But Mills did not escape his share of adverse criticism. In the Charleston Courier of May 24, 1822, there appears a protest against the building of a powder magazine in the vicinity of Charleston.

For a number of years preceding his retirement, he served as "Architect of Public Buildings" in Washington, D.C. The nation was more ready to accord him recognition of his art than his own state. However, the certificate of registration of the South Carolina Board of Architectural Examiners today is dedicated and inscribed to his memory.