One hundred twenty-nine years ago yesterday, Lewis and Elizabeth Burgess White of Kingstree, South Carolina, welcomed their first child into the world. They named him Amos Earl Mordecai White, and little did they know on the day of his birth, November 6, 1889, that before he was nine years old, he would face a great tragedy that would ultimately lead him to a life that was I'm sure totally beyond their wildest dreams.

We don't know what happened to Lewis, but we do know that Elizabeth White, a teacher in the African American schools in and around Kingstree, died shortly before Amos' ninth birthday. The Rev. Daniel Jenkins, who is well-known for the orphanage he started in Charleston, also preached on a circuit that included a church in Kingstree, apparently the church the White family attended. Young Mordecai, as he was called then, was admitted to the Jenkins Orphanage, where he would learn both printing and music, things that would support him for the rest of his long life.

The Jenkins Orphanage was known for the bands Parson Jenkins produced. They played on a worldwide stage, one of them playing the Hippodrome in London. Amos White was not in that band as he was not allowed to play an instrument until he was almost 14 because he suffered greatly from hay fever. He was, however, a member of the bands that played in Theodore Roosevelt's second inaugural parade in 1905; at William Howard Taft's inaugural parade in 1909, and actually led the band in 1913 in Woodrow Wilson's inaugural parade.

In his early 20s, White eloped with Parson Jenkins' daughter, settling in Jacksonville, FL, where he worked as a printer and continued to play trumpet and cornet. After 10 months there, he was asked to become director of the Jacksonville Concert Band, the second largest band in Jacksonville. The band gave concerts in the park every Sunday, a tradition White would continue many years later in Oakland, CA.

White later played in the circus band for the Cole Brothers Circus, one of the leading circuses of that era, and with a number of minstrel shows. When the United States entered World War I, White enlisted, becoming General Smedley Butler's bandmaster. The band serenaded General John J. Pershing four times during the war. Toward the end of the war, the band was sent to Le Harve, France, where it played for various occasions, including the sailing of troopships for the United States.

Returning to the States at the end of the war, White moved to New Orleans in 1919. There he got a job as a printer and began making a name for himself with the jazz bands. Jazz great Papa Celestin gave him his first real break, although White later said in an oral history, prepared by Tulane University in 1958, that all he could do was read the music, occasionally playing it with a little variation. But it didn't take him long to get into the New Orleans swing of things. While with the Celestin band, he played with a young Louis Armstrong. White remembered that they played many New Orleans jazz funerals in those days. Louis Armstrong later joined the famed Fate Marable Band, and after he headed north to Chicago, he was replaced as lead trumpet by none other than Amos White, who was later, White admitted, fired by Marable.

White was playing with the Marable band when it recorded Frankie and Johnny and Pianoflage. In his oral history, White notes that those two recordings were "a mess," because everyone was trying to outblow each other. However, a more recent critique of those recordings notes, "If there was a roof present, Amos must have blown it off. The ferocity and beauty he brings to bear is colossal in its impact."

At some point White organized the Imperial Orchestra for the city of New Orleans at the request of Armand Piron. The band played for circus acts in the park and for dances at the pavilion. In 1924 he formed the New Orleans Jazz Creole Band.

He left New Orleans in 1927. moving to Arizona, where he stayed until 1934 when he moved to Oakland, California, his home until his death in July 1980, just a few months shy of his 91st birthday. While in California, he taught music, directed his own band in weekly concerts in the park, and often played with other old New Orleans greats.

A jazz column in the Milwaukee Sentinel in 1965 noted that "veteran trumpeter Amos White, who played with many of the historic New Orleans bands, has made his first recordings." That music is still available online and on CD. You can listen to Amos play with his band and sing Sister Kate here.

The May 19, 1969, San Francisco Chronicle stated, "Sharing the stand with Pops Foster the other night was Amos White, a cornet and trumpet player, who is a mere 75. Amos White has not been playing much recently due to new dentures, but when he does come in, it is loud and clear. The musicians in the band tell of one night when he and Pops disagreed about a musical point. "Now, George," 75-year-old Amos said, to the 72-year-old Foster, "You listen to me. I'm older than you."

When George "Pops" Foster died in November 1969, his funeral was held the day before Amos White's 80th birthday. Again from the San Francisco Chronicle: "He was a very fine man and certainly ahead of his time," said Amos White, who will be 80 tomorrow and still plays trumpet at Oakland's De Fremery Park. "No, there aren't any of the old bands around anymore," White said. "I have to go down to the union hall nowadays and scout around for some men who know how to play the old way.

"White, as alert and as erect as he had been in World War I when he had been General Smedley Butler's bandmaster, smiled kindly when a white reporter asked him why nobody, hardly, was playing his kind of music anymore. "Why," he said very gently and without a trace of bitterness, "because you boys stole it from us."

White spent his later years trying to ensure that the old music would not be totally forgotten. In April, 1972, he took part in a weekend course on Ragtime at the University of California's Berkeley campus. He, along with piano greats Eubie Blake and Earl "Fatha" Hinds, engaged in discussion and offered reminiscences.

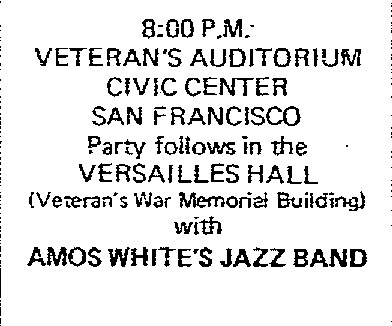

Ad from The San Francisco Chronicle, October 31, 1976.

On October 12, 1977, The San Mateo Times ran this article: An evening of New Orleans-style jazz, featuring 88-year-old Amos M. White and his jazz band will be presented at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art on October 12 at 8 p.m. in the museum auditorium. Admission is free. Amos M. White represents living history, having played trumpet with the great jazz musicians of the past 80 years. He will have a lecture and demonstration of the roots of jazz. Under the direction of Amos M. White and his grandson, Eddie 'Snakepit' Edwards, the band will play a variety of old and new jazz. Together Mr. White and his grandson will present 123 years of the music that has inspired generations of American musicians.

In 2006, Eddie Edwards, an alto saxophonist himself, recorded an album of his own. One of the cuts on the album is titled Grandpa Amos. You can hear it here.

In Tulane's oral history project–undergoing an update and not currently available online–White indicated that he well understood that had he not been orphaned at an early age, he would have never become a musician.

While most Kingstree residents had never heard of Amos White until Cassandra Wiliams-Rush wrote a tribute to him, published in The News in January 2017, he was listed as one of South Carolina's Jazz Greats in a full-page discussion of jazz in The State on June 28, 1964. The paper stated. "Amos White, a Jenkins' Orphanage alumnus, was born at Kingstree in 1899 (sic), in 1921 replaced Louis Armstrong in the Fate Marable River Band and in 1924 formed the New Orleans Creole Jazz Band."

It seems well past time that the Town of Kingstree recognize in some permanent way the contributions of its native son to the jazz world. The form that recognition takes could be a worthy joint project for the town's Main Street Program and the Williamsburgh Historical Society.

1 comment:

Linda-- thank you for paying tribute to "Grandpa Amos." My name is Steven and I am helping my friend Eddie Edwards archive/share his music, video and art on his website (www.snakepiteddie.com). Eddie asked me if it'd be okay to repost the article on his website, of course, linking back to your website. Grateful for stumbling upon your terrific website and looking forward to diving in!

Post a Comment