As the world struggles to slow the spread of Covid-19, or novel coronavirus, it's worth remembering that while many of our younger residents have little to no experience with epidemics and quarantines, to our ancestors these were not unusual occurrences.

A smallpox quarantine sign.

A 1918 story in the Charleston Evening Post, written in the midst of the influenza pandemic, noted that citizens of the United States had lived through five epidemics, beginning in 1831. The 1831 pandemic was apparently known as Russian Cholera. The only other date given was that the most recent flu epidemic had occurred in 1889-90.

We know from The County Record that a yellow fever epidemic held Charleston in its grip in 1897. The whole city was quarantined, and armed guards were stationed on all roads leading to Charleston. There were many rumors in Williamsburg County that one of those guards was posted at Lane.

Later in 1897, small pox was prevalent in some areas of the state, prompting County Record editor Louis Bristow to state, "Nearly all the towns in the state are requiring the citizens to vaccinate, as there is small pox within our state limits. Why does not Kingstree take some action on this matter? While there is no immediate danger, it is well to guard against a possible epidemic."

A few years later, in February 1900, a small pox outbreak in Lake City caused the Kingstree Town Council to call a special meeting in which a quarantine was issued for anyone coming from Lake City. Roadways were guarded, and the police met every train that stopped in Kingstree. No one who had been in or come through Lake City was allowed to get off in Kingstree. Several people were turned away during this time. At that time, Town Council ordered that all citizens would be vaccinated. The vaccine was free to anyone who was unable to pay. Refusal to comply with the order could result in a fine of $20, or 20 days in jail, or 20 days of hard labor on the chain gang. The quarantine was in effect until mid-March.

The next year, Kingstree became the target of many rumors as students at the Kingstree Academy began to suffer from a mysterious illness that caused skin lesions. None of them felt particularly ill, and little attention was paid to it until Headmaster W.W. Boddie began to suffer symptoms himself. He closed the school and called in the State Board of Health. Dr. James Evans arrived from Columbia and diagnosed the illness as varioloid, a very mild form of small pox. Rumors quickly spread. Charles Wolfe, who owned a paper in Georgetown, as well as The County Record, was in Georgetown that week and noted that he was hearing on the street that there were 25 diagnosed cases of small pox in Kingstree and that everyone was in danger. Within a couple of weeks, symptoms had abated, and no new cases appeared. By the end of the month, the Circuit Judge decided to hold court in Kingstree, although it was noted that jurors coming into town from the country were still quite nervous about the possibility of contracting the disease.

In 1903, a single case of small pox was confirmed in Fowler, 10 miles east of Kingstree. The Town of Kingstree enforced a strict quarantine, not allowing anyone from Fowler who had had contact with the patient or anyone in the patient's family to enter the city limits. The town again set up a quarantine in 1904 when several cases of small pox were confirmed on the other side of Black River.

Typhoid fever was an almost constant presence in Kingstree during wet summers. Many people thought that the cause was germs trapped in the earth, that were released when farmers or gardeners broke ground. Charles Wolfe, who himself suffered from tuberculosis, and must have lived in constant fear of contracting typhoid, editorialized often on the ills of breaking ground before a certain date.

Typhoid claimed the life of George S. Barr, 46, who owned Barr's Hotel next door to the courthouse. It also contributed to the death of former sheriff, Joseph Brockinton, who died of a heart attack shortly after suffering from typhoid. Both Dr. W.G. Gamble and Dr. Liston Bass Johnson came very close to dying from the disease but survived.

Cases of infantile paralysis, or polio, were first noted in the United States in 1911 and 1912. It was not until 1916, however, that it reached epidemic proportions, particularly in New York City. Dr. Walter Harper left Kingstree to go to Riverside Hospital in New York to help with the huge number of children who were suffering from polio. Shortly afterward, Martha Gordon and Hessie Mouzon followed him to offer their assistance as nurses. In South Carolina, children under 16 could not travel by train unless they had a "Certificate of Health," issued by a doctor. The Town of Kingstree also required this certificate before it would allow visiting children to enter the town limits.

That summer 27,000 children in the United States were affected by the disease, with 6,000 of them dying. Two thousand of those deaths were in New York City. There were 81 cases in South Carolina that year. Polio did not return in epidemic proportions until 1921, when future President Franklin D. Roosevelt contracted it. During the Depression and World War II, there were few outbreaks, but there were epidemics again in 1946, 1950, and 1951. From 1916 until 1955, July, August, and September were considered polio season. Sunday School classes were canceled, movie theaters banned children under 16, and summer birthday parties were postponed until cooler weather. It was not until the early 1960s, after the Salk and Sabin vaccines were widely in use, that parents were finally able to feel some measure of reassurance that their children were safe.

It is hard to find information on how Kingstree weathered the "Spanish Flu" pandemic of 1918 as there are no issues of The County Record available from March 1918 through February 1919. We do know that Rhett M. Driggers, 25, a Charleston native, working as a pharmacist in Kingstree, died of double pneumonia, a complication of the flu in October 1918. From other newspapers, we know that one mother and daughter also died, as another daughter who lived in another town came for their funerals. It is also possible that Luna Tribble Arrowsmith may have had a bad case as her mother left Abbeville to come to Kingstree to care for her.

An advertisement from Southern Bell Telephone in the October 8, 1918,

Charleston Evening Post acknowledging service interruption due to the flu pandemic.

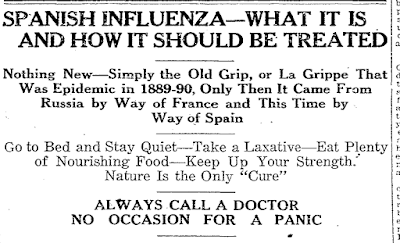

The epidemic began with a number of mild cases of influenza in Spring and Summer 1918. However, by September and October, many who had the flu also developed pneumonia, which was fatal. But even in September, the city health officer in Charleston said, that the Spanish Influenza was nothing worse than the common or war garden variety of grippe. The U.S. Health Service encouraged citizens to be cheerful, go to bed, take a laxative, and keep up their strength as nature was the only cure. Persons wishing to avoid the disease were encouraged to use Vicks Vapor Rub.

By October, it was evident that the epidemic was growing worse. Persons in charge of public buildings were told to keep all doors and windows open and to avoid over-crowding. In Charleston, funerals could be held in cemeteries but were not allowed in homes or churches. Schools closed, some for a month; others in more-hard hit areas of the state were closed for 15 weeks.

Headline from a story in the October 10, 1918, Charleston Evening Post.

Politics was a factor in the 1918 pandemic, as well. In the October 28, 1919, issue of the Charleston Evening Post, this editorial comment appeared: Strange that no Republican has yet accused President Wilson of starting the influenza epidemic which has prevented the holding of campaign meetings.

And although the Spanish flu gradually built from mild cases to a raging pandemic over a number of months, it burned itself out at a much faster rate. By the end of October, there were dramatically fewer new cases. An overall view of the state situation, published in the Charleston Evening Post on November 2, 1918, noted that many towns were lifting quarantines. The Town of Kingstree had decided to leave its quarantine in place for an additional 10 days to be cautious. Figures vary, but approximately 80,000 South Carolinians contracted the Spanish Flu, with 14,250 of them dying.

1 comment:

Great article!

Post a Comment